Success Story: Many Policing “Pretexts” Eliminated in Virginia

During the 2020 Special Session, Virginia passed new legislation that eliminates many of the most commonly used pretexts, which police use to conduct investigations of “hunches” for which they have no evidence. Those “hunches” are often driven by implicit if not explicit racial bias, leading to dramatic racial disparities in traffic and pedestrian encounters. The law (HB 5058 and SB 5029 - Marijuana and certain traffic offenses; issuing citations, etc) which changes many minor traffic and pedestrian violations from primary offenses into secondary offenses, and prohibits stops based on the odor of marijuana, went into effect on March 1, 2021. This means that while these infractions (other than marijuana) remain against the law, they are not a reason that a person can be stopped. If a person is stopped for another reason, they may still receive a ticket, however.

That said, the new marijuana legalization bill which goes into effect on July 1, 2021 created several new laws (e.g. “open containers” in vehicles, public consumption), and these may be used as a pretext for police stops. Some of these concerns were addressed in “Legal marijuana in Virginia is just the first step,” an op-ed published in the Washington Post from a number of advocates, including Justice Forward Virginia.

As noted above, pretextual policing is the practice of stopping someone for one reason (often a minor traffic violation) in order to conduct investigations unrelated to the reason for the stop. In addition to traffic and equipment violations, police often stop pedestrians by citing the smell or marijuana or jaywalking. Once stopped, individuals and their vehicles are often searched, in hopes that police will find illegal items such as drugs or weapons. Pretextual stops are also used by police to find out if the person has a warrant for their arrest.

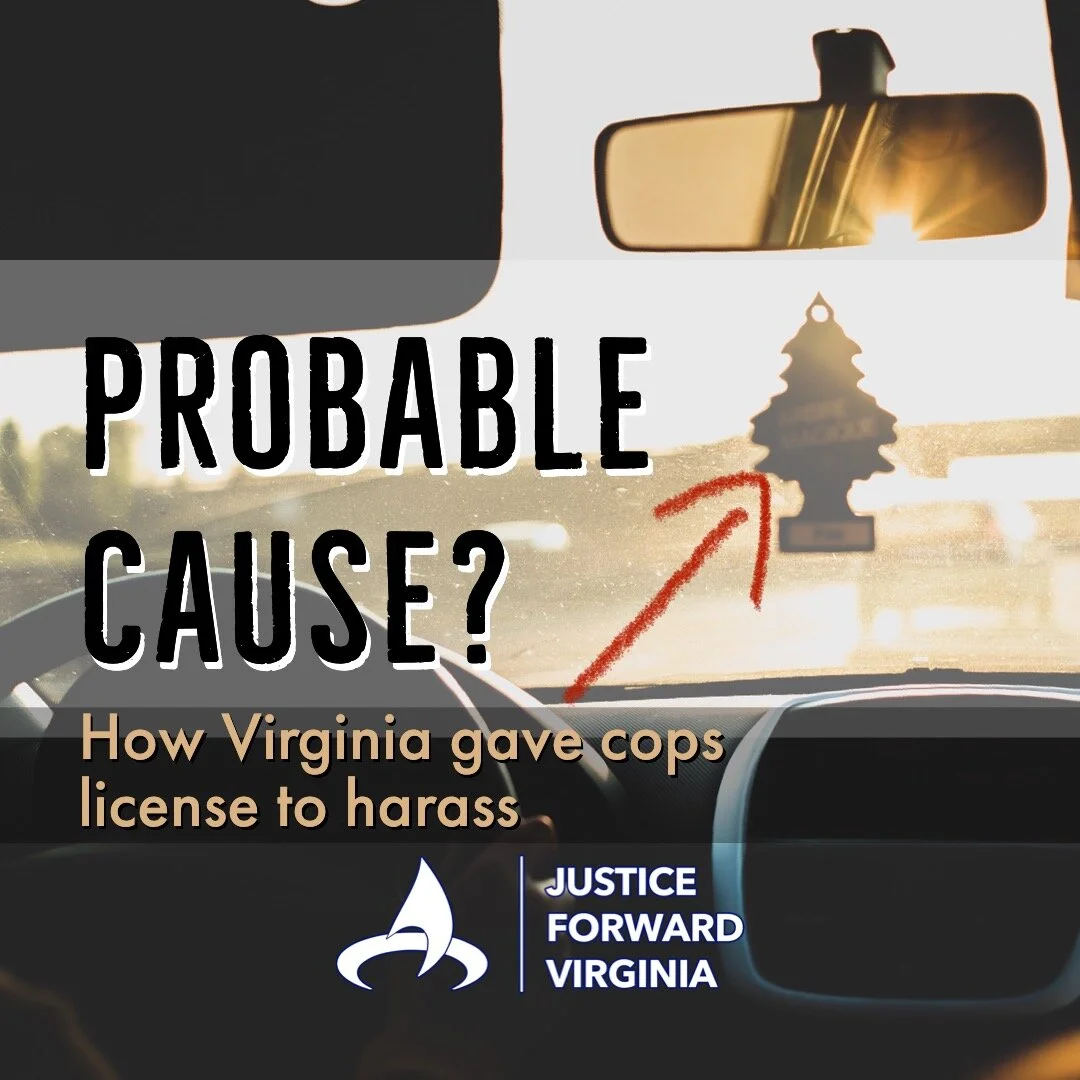

Pretextual policing has historically been used to enforce laws based on stereotypes, with police acting on implicit and explicit bias to stop and search people who “looked suspicious.” Although the law does not allow police to stop people explicitly because of their race, it does allow them to do so if they come up with a “cover story”; some race-neutral reason that in actuality the officer did not care about. These reasons include the hundreds of infractions listed in the traffic code, such as having an object (like an air freshener) hanging from the rear view mirror, dark tint or loud exhaust. The reasons also often include minor criminal misdemeanors, such as jaywalking and marijuana, or more specifically the odor of marijuana (something nearly impossible to dispute after-the-fact).

Pretextual policing is a matter of racial justice. Black and Brown people are significantly more likely to be stopped and investigated for these kinds of infractions, so changing the law will reduce overpolicing of people and communities of color. There are many anecdotal examples that demonstrate the racial disparities in pretextual stops, but getting accurate data is challenging. A recent study that looked at video from LAPD stops showed that 23% of searches were not even documented. Additionally, race of the person stopped is often not captured. A new data bill passed by the General Assembly in 2020 should improve data collection, and future evidence-informed policymaking efforts.

Incidents where pretextual stops have escalated and ended tragically have been widely publicized over the past several years and months. But until the assault of Lieutenant Nazario in Windsor, VA this year, coverage of incidents involving pretextual stops typically focused on the violent endings rather than the reasons for the initial stops. We don’t hear about the vast majority of pretextual stops.

Philando Castile was shot and killed by a police officer after being stopped because he had a broken taillight. During the prior 14 years, he had been stopped 46 times.

Sandra Bland was arrested and died in jail after being pulled over for failing to use a turn signal when changing lanes.

Walter Scott was shot and killed by police after being stopped for a faulty brake light.

Derrick Thompson was forcibly removed from his car and assaulted by Fairfax County police after being stopped for an expired inspection. The police also claimed they smelled marijuana, but none was found during a search. Before he was pulled from the car, the police officer yelled at Thompson that “You’re going to get your ass whooped in front of fucking Lord and all creation.” He then looked at the camera phone filming the incident and said, “Watch the show, folks.”

Now that the law has gone into effect, many common traffic and pedestrian violations no longer provide a basis for the police to stop individuals. If a person is stopped for one of the reasons listed below (and a number of others), any evidence discovered will be inadmissible.

Defective Equipment: Tail Lights / License Plate Lights; Brake Lights

Police regularly make stops for having one of two license plate lights out. Although the tail light statute says there must be a white light (singular) that makes the plate visible from at least 50 feet, the more general defective equipment statute makes it unlawful to have or use defective equipment on your vehicle. So, even if the license plate is illuminated and visible, police can still stop you if one of the bulbs is out. A similar issue arises where one of three brake lights is out. The brake light statute does not require a third light, but police can stop for defective equipment if the third light is not working.

Police regularly stop people under this statute for hanging objects from the rearview mirror, including parking permits, rosaries, air fresheners, and perhaps most egregiously, Disabled Parking Placards.

Loud Exhaust *UPDATE July 1, 2022 Prohibition repealed during 2022 General Assembly

Police can stop a person if an officer says the car was making “excessive levels of noise.” The law, however, does not define how much noise is “excessive”.

Police frequently stop vehicles based on an officer’s visual estimation that the window tinting is too dark. In order to prove such a charge, officers actually have to measure the tint with a standardized device, but they often make these stops even if they do not have the device available.

Expired registration or expired state inspection

Gone are the days of police setting up shop on congested roadways during rush hour on the first day of the month to ticket everyone whose registration or inspection expired the day before. Under the new law, you still need to update your registration and inspection on a timely basis, but you can’t be pulled over for it until after a grace period of several months (you can be ticketed, though, if you’ve been stopped for something else).

Pedestrian in Roadway/Jaywalking

Police can also stop pedestrians based on pretext. Because a little mild jaywalking is incredibly common, particularly in more urban areas, police can stop pretty much anyone who “looks suspicious” to an officer.

The Smell of Marijuana

As the nation has learned in 2021, with the pretextual stops of Lt. Nazario and Daunte Wright, among others, ending pretextual policing practices once and for all might be the key to police reform. Although removing common pretexts represents tremendous progress, it will not solve the problem entirely. There remain hundreds more traffic and misdemeanor offenses Virginia police can use to act on their “hunches,” and over time they will use how to learn them.

This is why in 2021-22, Justice Forward Virginia will continue to make ending pretextual policing a priority. In particular, we will seek to prohibit requests for consent searches after traffic stops, and potentially prohibit warrant checks, as well. Eliminating the two most common objectives of a pretextual stop will make traffic enforcement about traffic enforcement again, and the safety of motorists, rather than a opportunity for evidence-free harassment of Black and Brown motorists. This would also likely preclude the need for Virginia to establish a civilian traffic enforcement agency, which would cost considerably more money. In addition to the ban on consent searches, Justice Forward will also seek to repeal or amend many of the hundreds of over-enforced criminal misdemeanor offenses that are used as pretexts outside of the traffic context.